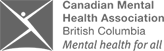

Health

As suggested by our name, Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses, we are concerned with health. But what is “health”? Is it an objective reality that can be measured independent of the person? Or is it a subjective judgement such that it might vary across individuals, times and cultures? Or does it embody elements of both? While we do not attempt to resolve all the complex issues involved or offer a tight definition of health, we acknowledge the conception of health embedded in the constitution of the World Health Organization.

Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization, Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100).

This view recognizes the experiential and phenomenological aspects of health that go beyond a lack of sickness, injury or disability.

Within Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses, we tend to challenge narrow definitions and seek to draw attention to the complex array of biological, social, political, environmental and historical factors that influence health and well-being.

Mental Health

Mental health is:

The capacity of each and all of us to feel, think and act in ways that enhance our ability to enjoy life and deal with the challenges we face. It is a positive sense of emotional, social, intellectual and spiritual wellbeing that respects the importance of culture, equity, social justice, interconnections and personal dignity (Joubert & Raeburn, 1997). Produced through dynamic interaction between individuals, groups and the broader environment (Epp, 1988), mental health is the foundation of well-being and effective functioning for individuals, families, communities and societies (GermAnn & Ardiles, 2009).

As we become more aware of how our health is intricately connected to mental, physical and social strands of our existence, it becomes ever more apparent that mental health is critical to the overall wellbeing of individuals, communities and societies. Unfortunately, in our communities and on our campuses, mental health is not yet regarded with anything like the same importance as physical health.

While it is operationally convenient for purposes of discussion to separate mental health from physical health, this is a fiction created by language. Most “mental” and “physical” illnesses are understood to be influenced by a combination of interdependent biological, psychological and social factors. Furthermore, thoughts, feelings and behaviour are now acknowledged to have a major impact on physical health. Conversely, physical health is recognized as considerably influencing mental health and well-being (The World Health Report 2001. WHO). Likewise the use of psychoactive substances influences health through biological, psychological and social mechanisms.

So, while Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses focuses on, “mental health and substance use,” we do so with full recognition of the complex interconnected web of well-being. For us, these are not separate issues but important and entwined aspects that need to be taken into account as we seek to build healthy campuses.

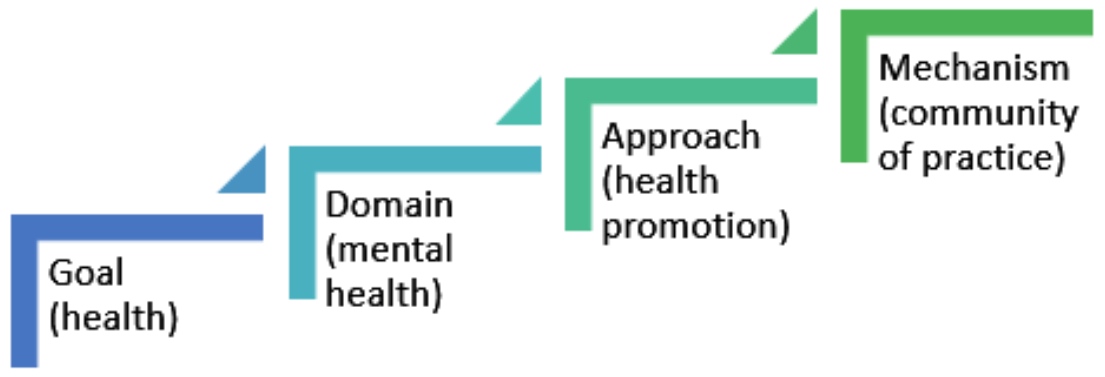

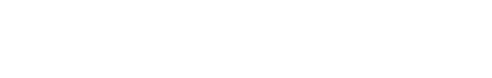

Neither are these simple binary concepts such that you are either healthy or you are not, a drug is either good or bad. The impact of using any particular drug can be anywhere between “beneficial” and “clearly harmful” depending on a range of factors related to the drug, the person and the context of use. Furthermore, any particular use of a drug may have positive effects in one area of well-being while also posing risks in another area at the same time (think “side-effects”). Likewise, mental health is not simply the binary opposite of mental illness. As the following model (based on Keyes, 2007, 2011) suggests, one can “thrive” despite experiencing illness (e.g., function purposefully and relate well to others though deeply troubled by personal anxiety) while another may be “barely surviving” in the absence of any particular illness, injury or disability (e.g., doggedly persevere in the face of unremitting grim hardship without falling into depression).

It is within this comprehensive understanding of well-being that Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses draws attention to, and supports action around, “mental health and substance use.”

Health Promotion

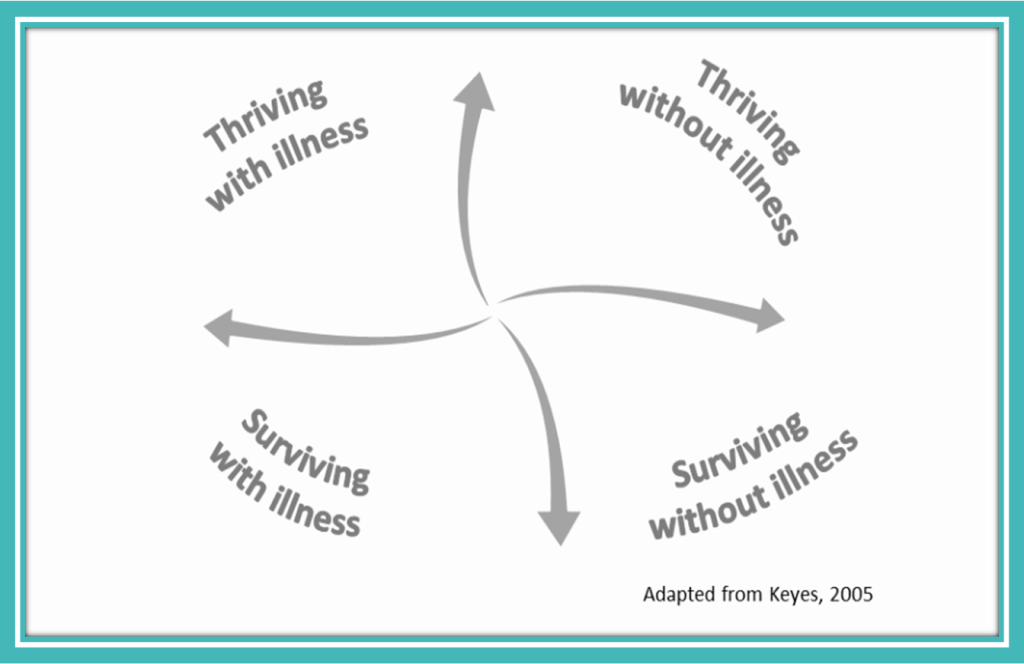

Health promotion encourages us to embrace well-being and increase our control over how we experience everyday life. It is therefore less about preventing disease than about helping us manage our life situation, whatever it may be, and reach our full potential. But how does it work? Effective health promotion strikes a balance between personal choice and social responsibility, between people and their environments. In other words, it does not put the onus for good health on the individual alone. Health promotion pushes us beyond a disease-oriented “individual lifestyle is key” concept of good health. It focuses attention on things outside our individual selves—the social, economic and environmental factors that impact our attitudes, decisions and behaviours. These play out at every level of society, from the individual through family and community to a national and even global scale.

This multi-lens perspective can be applied in a variety of settings, such as workplaces, neighbourhoods, cities, schools or campuses, to help promote ways we can improve our experiences in our everyday environments. Health promotion may also be applied to common but complex human behaviours such as substance use. But since mental health is determined to a large extent by social and economic factors, success in promoting mental health and well-being can only be achieved through the engagement of and support from the whole community and the creation of partnerships with a wide range of agencies, organizations and sectors (WHO, 2005a: 24).

In this emphasis on environment and structural determinants, it is important not to lose sight of the individual. Health promotion involves empowering individual citizens to engage in the community in ways that allow them to manage their own wellbeing and support their fellow citizens in this mutual process.

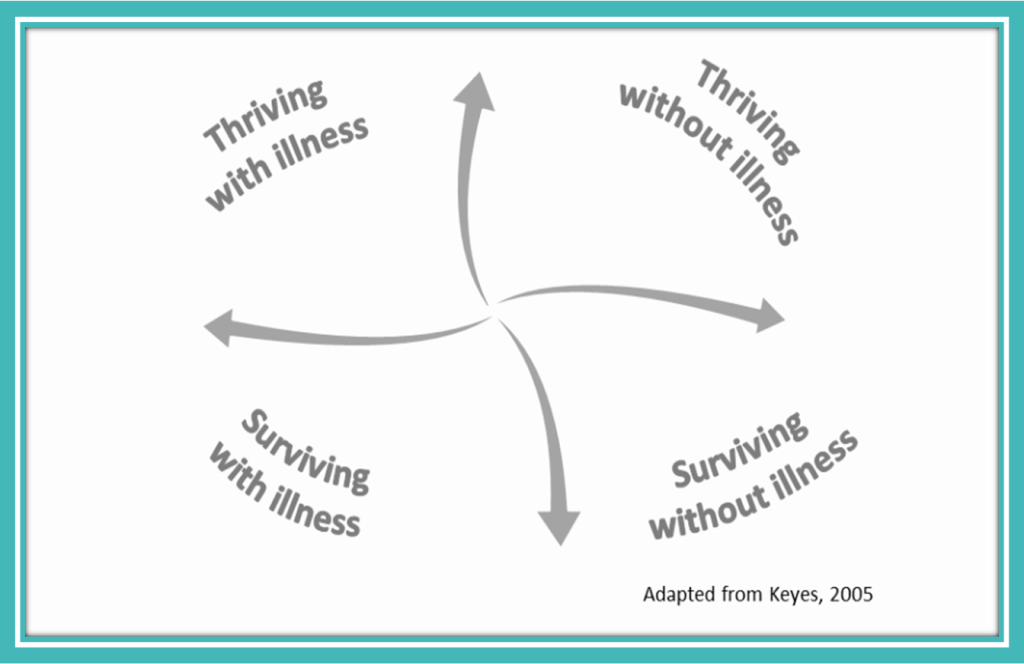

View a dynamic model of mental well-being for assessment by Lynn Friedli taken from the Mental Well-being Impact Assessment Toolkit below:

Community of Practice

We often refer to Healthy Minds | Healthy Campuses as a community of practice or as promoting the emergence of communities of practice on campuses.

The expression “community of practice” (CoP) was first used in 1991 by Etienne Wenger and Jean Lave to refer to a group of people who share a common concern, set of problems or domain of interest and who collaboratively develop a common set of practices with which they work together towards a common goal. But the roots of CoPs go much deeper. One can argue that the foundation of the “community of practice” concept first emerged in Aristotle’s discussion of “practical” knowledge in book six of the Nicomachean Ethics. This discussion is taken up in the debates about knowledge and action within critical theory and the field of hermeneutics (cf. Gadamer and Habermas).

The members within a CoP maintain a horizontal partnership with mutual relevance and are driven by passion and self-interest. The CoP involves multiple levels of participatory involvement, from the core group who lead and coordinate community activities to peripheral and transactional members who simply observe or may benefit from the community’s efforts. Members also move fairly fluidly between levels of involvement and in and out of community roles.

One benefit of a “community of practice,” is that it helps us avoid restricting our conception of knowledge to either theoretical constructs or technical control mechanisms. While incorporating these elements, a “community of practice” seeks what Habermas calls “a rational consensus on the part of citizens concerning the practical control of their destiny” (Theory and Practice, 1973).

Learn more about what a “community of practice” is and how to grow a vibrant community by clicking on the Prezi presentation below.